As one of the oldest wildlife laws in U.S. history, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act has protected millions, possibly billions, of birds since its inception in 1918. But the Migratory Bird Act, or MBTA, isn’t just ancient history. It’s important to know the basics of this law now to support the declining bird population, and protect ourselves from criminal penalties.

A Brief History of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA)

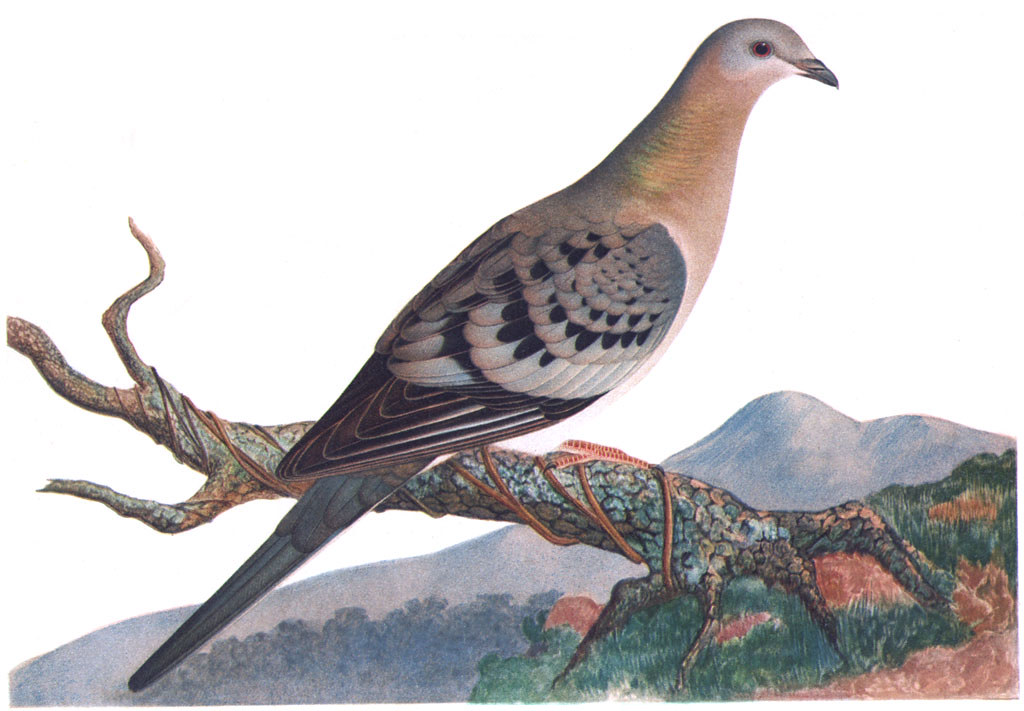

In the 1800s, barely any regulations were in place to protect wildlife, and hunters were decimating the bird population, Though hunted for sport and food, the birds were also killed for their plumage. As a result, the last part of the century saw the extinction of many bird species, including Passenger Pigeons, Labrador Ducks, and Carolina Parakeets.

Towards the turn of the century, conservationists fought to regulate bird hunting, resulting in the Lacey Act of 1900 and the Weeks-McLean Migratory Bird Act of 1913, which put migratory birds under government protection for the first time. Three years later, the U.S. would sign a treaty with Great Britain to stop the hunting of all insect-eating birds and creating a special game bird hunting season. This led to the MBTA in 1918, which is still in effect to this day, and prohibits people from pursuing, hunting, taking, capturing, or killing migratory birds and their nests, eggs, and feathers.

Today, the risk to wild birds has evolved from feathered hats to habitat loss, with the MBTA at the forefront of bird conservation efforts.

What the MBTA Prohibits

Although we won’t go through the law in its entirety here, we want to highlight parts of the MBTA that might affect us in our daily encounters with wild birds.

The MBTA makes it unlawful to “pursue, hunt, take, capture, kill, possess, sell, purchase, barter, import, export, or transport any migratory bird, or any part, nest, or egg of any such bird, unless authorized under a permit issued by the Secretary of the Interior.”

And while our readers are nature lovers who wouldn’t dream of harming wild birds or running afoul of the law, it’s important to discuss some ways we may inadvertently violate the MBTA. Some points to consider:

- You cannot destroy or move an active nest of a protected bird species, even if it’s on your property. The only exception is if the nest poses a threat to health or safety or might cause property damage.

- You cannot keep a protected bird species in your care, including for rehabilitation. If you find a sick or injured migratory bird, or its eggs or young in distress, it’s important that you take the correct next steps. This includes contacting a wildlife rehabilitator in your area.

- You cannot take, or be in possession of, feathers from a protected bird species. If you wish to obtain feathers for educational purposes, you need a permit from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

What Happens if You Violate the MBTA

While there are some varying legal interpretations of the MBTA, and courts have made rulings based on violations with intentional vs. unintentional harm to birds, this is a federal law with real repercussions. Violations of this law are misdemeanors, which may incur fines of hundreds, sometimes thousands, of dollars and imprisonment.

Which Birds the MBTA Protects

Currently, the MBTA protects 1,106 bird species within the U.S., Canada, and Mexico, as well as Japan and Russia (based on international treaties). While the full list of protected species can be found on the U.S. Fish and Wildlife website, it’s important to note that most of the birds of the Big Bear Valley are protected under this law.

How the MBTA Has Helped Wild Birds

If you want to see the success of the MBTA, merely cast your eyes skyward. Many birds have been saved from extinction because of this law. For example, the Snowy Egret was once sought for its pristinely white plumage, used for women’s hats. Hunters killed hundreds of thousands of these birds, selling their feathers for $32 per ounce—and that’s 1886 prices! But with the MBTA enactment just in time to protect these beautiful birds, their populations have risen to 2.1 million today.

Other birds like the Wood Duck and Sandhill Crane also owe their now-stabilized populations to the MBTA. In fact, since the act was implemented, it has restored the populations of many birds, including herons, egrets, and other waterfowl. The MBTA has also acted as a watchdog to ensure that oil, gas, and energy companies develop and follow industry guidelines that protect migratory birds.

Protecting Birds on an Individual Level

The MBTA has proved a vital bulwark that has slowed the decline of the bird population, rejuvenating some species from almost extinct to thriving. But, on a personal level, what can we do to help our local birds? Here are some helpful resources:

- How You Can Help the Declining Bird Population

- How Climate Change Affects Wild Birds (and What We Can Do)

- What to Know About Wild Birds and the Law

- How to Help an Injured or Sick Wild Bird

- I Found an Orphaned Baby Bird, What Do I Do?

- Which Human Foods are Bad for Birds?

- Poison-free Pest Control

- How to Plant a Hummingbird Garden

- Regenerative Wild Bird Habitats: Why Needed and How to Help

- 5 Ways to Prevent Window Collisions and Keep Birds Safe

- How to Help Birds Survive Wildfires: FAQs and Tips

- Why Keep Your Cats Indoors?